On October 25, 2025, I was officially released from the custody of the Federal Bureau of Prisons to begin my 3 years of supervised release with the Department of Justice. After seven months in actual prison, a few months in a halfway house, and the remainder on home confinement and a final six-month home detention, my 24-month custodial sentence (May 20, 2024 – October 25, 2025,) was over.

As a formerly incarcerated woman and current sociology student, I’ve seen how the criminal justice system doesn’t just punish, it structures inequality. Using Conflict Theory, I’ll show how power and privilege shape sentencing and reentry. Through Labeling Theory, I’ll explore how the “felon” label blocks reintegration, even for those, like me, who received leniency. My story isn’t one of deep oppression, but of proximity: I witnessed racial and gender disparities up close, including generational trauma that incarceration deepens rather than heals. I now use education and advocacy to support women at every stage of the justice system.

School Supplies

My Story: A Lens of Proximity, Not Oppression

My sentence began May 20, 2024. I surrendered to FCI Victorville Camp and was assigned the top bunk in a room with Amy Wilson (not her real name), a woman serving 156 months who has been inside for over seven years. Within weeks of my arrival, Amy’s daughter overdosed and lay on life-support 45 minutes from camp. Despite pleas, Amy was denied a furlough to say goodbye. By the time administrators considered it, her daughter had passed. I wrote about that unbearable grief in a blog post titled “Queen Bee” last year. https://gracedignityandcompassion.com

This October, history repeated itself in an even crueler way. Amy’s son, also overdosed and spent days on life-support. This time she was granted a furlough and got to hold his hand. He was brought out of the medically induced coma and the breathing tube was removed during her visit. She was able to tell him she loved him, and to keep fighting. When it was time for her to return to camp, he cried, “I don’t want you to leave.” He died the day before Thanksgiving. In less than eighteen months, Amy has lost both of her children to drug overdoses while she has been incarcerated, unable to be the mother she wanted to be because of the non-violent drug transportation crime she committed almost a decade ago.

These losses are not random tragedies. They are the predictable outcome of generational trauma compounded by mass incarceration: poverty, untreated addiction, childhood exposure to violence, and then decades-long sentences that rip families apart (Sentencing Project, 2024). As a middle-class white woman, I received leniency and access to programs Amy never saw. My proximity to her pain, not my own suffering, is why I speak. Research shows that formerly incarcerated people are far more likely to lose parents, siblings, or children while they’re locked away (Testa & Jackson, 2021). Amy’s story is painful proof of that.

Primary Theory: Conflict Theory

Conflict Theory views society as an arena of inequality where powerful groups create rules to maintain dominance (Encyclopædia Britannica, Sociology). Sentencing and reentry policies protect elite interests while controlling marginalized groups. The people who already have money and power usually don’t break the laws in the first place, because most of those laws were written to protect what they have. And on the rare occasions they do break a law, they have expensive lawyers, connections, and lighter consequences and often do not end up with a felony record. Poor people, especially poor women of color, don’t get that same shield. One mistake and the system swallows them whole. I lived it sitting next to women doing many, many years longer than I did for the exact same kind of case. According to conflict theory, those with power and wealth are more likely to obey the criminal law because it tends to serve their interests. In addition, they are better able than poor people to avoid being incriminated when they do violate the law (Encyclopædia Britannica, Criminology).

My 24-month sentence (most served in the community) with credits and programs stands in stark contrast to Amy’s 156 months for a similar nonviolent offense. Black and Latina women routinely receive decades longer than white women for comparable crimes (Starr & Rehavi, 2013). These disparities are not accidental, they sustain racial and economic hierarchies.

Reentry barriers continue the control. Felony convictions block housing, employment, and voting, ensuring formerly incarcerated people remain economically dependent. Formerly incarcerated women face unemployment rates up to 50% higher than men, with Black women earning roughly 40% less than peers five years post-release (Starr & Rehavi, 2013). When mothers like Amy lose custody or visitation, children are pushed into the same cycles of poverty and addiction that feed the prison pipeline. Exactly what generational trauma looks like under Conflict Theory.

My access to education and Rising Scholars reflects social capital most women inside do not have. Education reduces recidivism only when it is accessible. My lighter sentence and college path are privilege in action, not personal merit.

Secondary Theory: Labeling Theory

Labeling Theory argues that societal stigma amplifies deviance by shifting a person’s master status to “felon,” producing secondary deviance through rejection. For mothers inside, the label destroys family bonds and mental health. In contrast, labeling theory portrays criminality as a product of society’s reaction to the individual. It contends that the individual, once convicted of a crime, is labeled a criminal and thereby acquires a criminal identity. Once returned to society, he continues to be regarded as a criminal and is consequently rejected by law-abiding persons and accepted by other delinquents (Smith et al., 2022).

Amy’s story is labeling made lethal. Denied furlough to see her dying daughter, labeled too “high-risk” for compassion despite minimum-security status, she could only wait for news. The system labeled her children “at-risk” long before they overdosed, removing their mother for over a decade guaranteed the outcome.

Even in academia the label hurts. This semester in my Statistics and Probability class for sociology majors, the required 283-page workbook repeatedly used the word “convicts” in word problems. I was so angry I walked out of class one day. After I spoke with the professor, she promised the next edition will say “justice-impacted individuals” instead. Small victories matter, because language is the first place the label takes root.

We rewrite labels through action. Mailing crochet patterns, books, and FSA sheets counters the script with new identities: artist, student, mother, future. Education remains one of the strongest turning points in desistance research because it replaces “inmate” with “scholar” (Hall, 2015).

Data & Broader Context

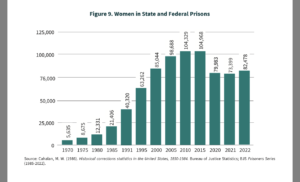

Women are the fastest-growing incarcerated population, up 585% since 1980 (Sentencing Project, 2024). The number of females in state or federal prison increased almost 5% from yearend 2021 (83,700) to yearend 2022 (87,800) then another 4% to yearend 2023 (91,100). Over 60% are mothers; prolonged separation dramatically increases children’s risk of incarceration and substance-use disorders (Bureau of Justice Statistics,n.d.). Formerly incarcerated women earn ~40% less than peers five years post-release. Black women remain incarcerated at five times the rate of white women (Sentencing Project, 2024).

Call to Action & Hope

I can’t fix the system but I can connect and amplify.

You can:

- Mail approved books or crochet patterns to incarcerated women. Message me for more information.

- Support reentry and job training programs.

- Replace “convict” and “felon” with “person” in everyday speech.

Learn more:

Prison Policy Initiative – Women 2024: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/women2024.html

Rising Scholars: https://risingscholars.fullcoll.edu/

Anti Recidivism Coalition (ARC) https://antirecidivism.org/

Conclusion

The system creates inequality through sentencing, labels destroy families through stigma and separation, and generational trauma claims the next generation while mothers remain locked away. Yet education, compassion, and community can interrupt the cycle. Every book I mail, every pattern, every conversation that replaces “convict” with “person” is sent not as a savior, but as a witness turned ally. Healing happens in community.

WCSG Annual Conference- Featured Panelist

References

Encyclopædia Britannica. (n.d.). Sociology. Britannica Academic. Retrieved December 4, 2025, from https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy.ivc.edu/levels/collegiate/article/sociology/109544#222969.toc

Encyclopædia Britannica. (n.d.). Criminology. Britannica Academic. Retrieved December 4, 2025, from https://academic-eb-com.ezproxy.ivc.edu/levels/collegiate/article/criminology/109546#article-contributors

Hall, L. L. (2015). Correctional Education and Recidivism: Toward a Tool for Reduction. Journal of Correctional Education, 66(2), 4–29. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=c594bcbf-eef1-3e19-ae5a-f3e7c36ca8da

Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-2022-statistical-tables

Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables | Bureau of Justice Statistics. (n.d.). Bureau of Prisoners in 2023 – Statistical Tables | Bureau of Justice Statistics. (n.d.). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/prisoners-2023-statistical-tables

The Sentencing Project. (2025, December 4). We change the way Americans think about crime and punishment. https://www.sentencingproject.org/

Smith, M. L., Hoven, C. W., Cheslack-Postava, K., Musa, G. J., Wicks, J., McReynolds, L., Bresnahan, M., & Link, B. G. (2022). Arrest history, stigma, and self-esteem: a modified labeling theory approach to understanding how arrests impact lives. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(9), 1849–1860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02245-7

Starr, S. B., & Rehavi, M. M. (2013). Mandatory Sentencing and Racial Disparity: Assessing the Role of Prosecutors and the Effects of Booker. Yale Law Journal, 123(1), 2–80. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=ad218cac-2179-359b-9d3f-77254d84a5ad

Testa, A., & Jackson, D. B. (2021). Family member death among formerly incarcerated persons. Death Studies, 45(2), 131–140. https://doi-org.ezproxy.ivc.edu/10.1080/07481187.2019.1616856